Back to my web page at http://www.claytoncramer.com.

Shotgun News, November 1, 2004, pp. 18-19

Gun Safety Regulation in Early America

I've just returned from a trip to the East Coast, completing some research for an upcoming book. One aspect to the history of gun ownership in America that has been somewhat overlooked is safety regulation. By safety regulation, I do not mean gun control laws intended to prevent responsible gun ownership or use, but laws whose purpose was to promote public safety.

Some of these laws, especially in the early years of settlement, required citizens to own guns, and in some colonies, to carry guns when traveling outside their village. (See my articles in the June 1, July 16, and August 1, 2001 issues of Shotgun News for details.)1 These were "safety regulations" in the sense that by requiring most men (and in some colonies, some women) to own guns, and in some cases, to carry guns, they made the entire community safer from external attack.

Today, however, I am writing about laws that are not too terribly different from reasonable gun safety regulations today--although at least some of them might not seem so reasonable today. For example, the Massachusetts legislature prohibited firing guns within the town of Boston at the 1713-14 session, because "by the indiscreet firing of guns laden with shot and ball within the town and harbour of Boston, the lives and limbs of many persons have been lost, and others have been in great danger, as well as other damage has been sustained..."2 If you wanted to hunt, or go target shooting, you had to leave town. There was no exemption for defensive gun use, but it does not appear that this law prohibited otherwise lawful emergency uses of a gun.

Gunpowder storage laws are another example of a safety regulation not so terribly different from laws we have today. Before the Revolution--and even for some time afterwards--quite a bit of American gunpowder was still made at home--and sometimes, those doing so were not terribly sensible about where they made it. An interesting item that I found from a 1957 article about Maryland gunpowder making manages, in a single paragraph, to convey how common pistols were, how few restrictions there were on who could have them--and how inappropriately some people chose where to make gunpowder. "An earlier explosion occurred on October 17, 1783, in the yard of a Mrs. Clement in Baltimore, where some gunpowder had been placed to dry. Three boys, two of them Negroes, went into the yard to clean their pistols. One of them carelessly fired his pistol near the powder, causing it to blow up. One boy was killed and the other two seriously injured."3

This, plus other accidents involving gunpowder, unsurprisingly led to regulations restricting the storage of gunpowder in cities. In 1797 Baltimore required gunpowder to be stored in public magazines.4 It is unclear if this requirement applied to all quantities of gunpowder or only quantities above a certain size. New Brunswick, New Jersey's 1813 ordinance regulating storage of gunpowder applied only to quantities of fifty pounds or more.5 Boston's 1821 ordinance (which was apparently not the first such regulation) licensed possession of more than five pounds of gunpowder within any building (residential or business) in the city. Wholesalers and retailers were regulated as to the quantities, storage methods, and public notice requirements, but quantities under five pounds were exempt from all regulation.6 (I find it interesting that the town where I lived for many years in California had the same limit on black powder in residences--five pounds. It would be interesting to trace the history of such laws, and see when this limit was first set.)

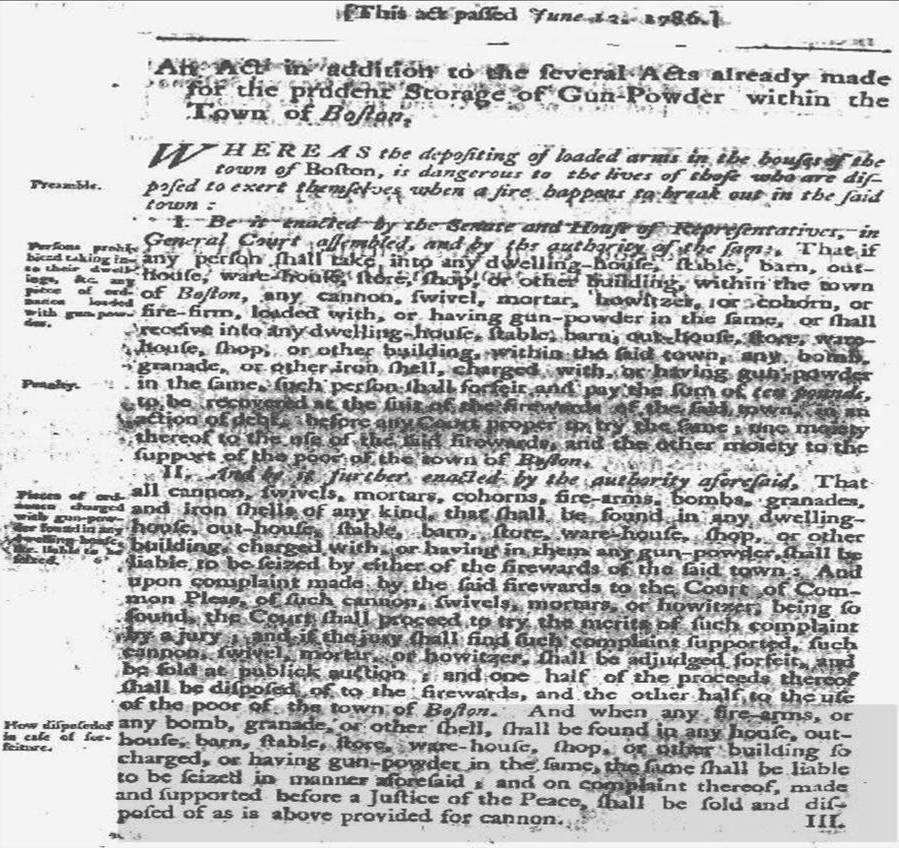

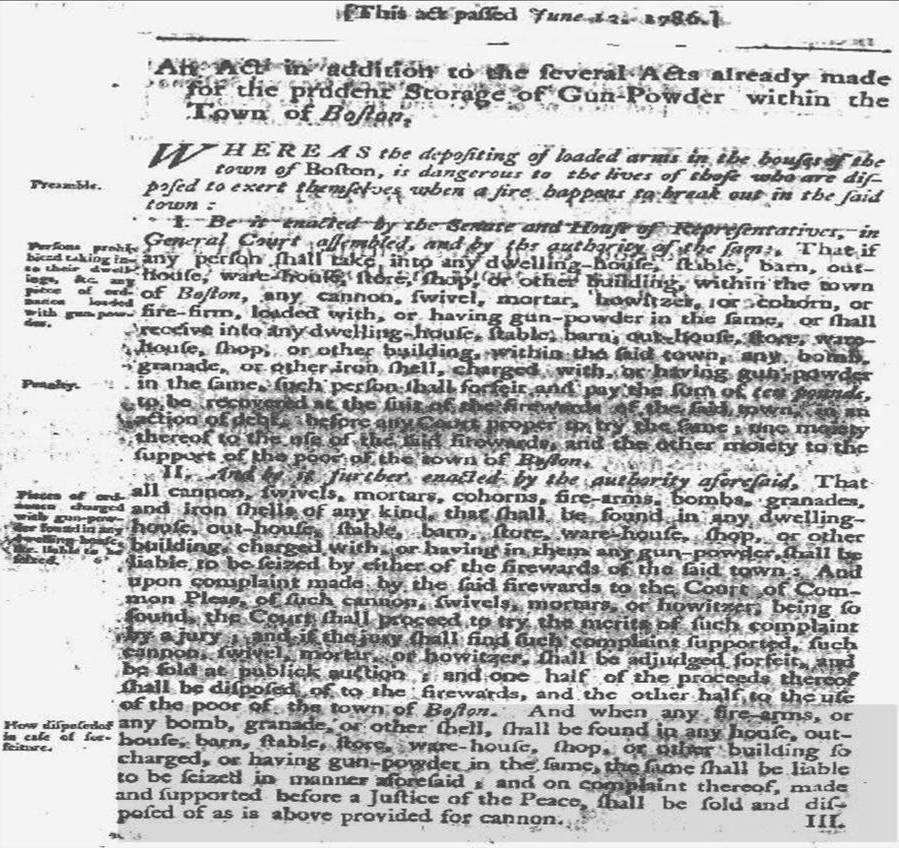

There is another safety regulation from Boston that is interesting not just for its history, but for how gun control advocates use it today as evidence in support of their position. A Massachusetts law of 1786 provided that within the city of Boston, it was unlawful to keep loaded "fire-arms, or any bomb, granade, or other shell... in any house, outhouse, barn, stable, store, ware-house, shop, or other building...." Other sections apply this to "cannon, swivels, mortars" and other military ordnance, and prohibit bringing any loaded gun into a building. Professor Saul Cornell, an antigun historian, has pointed to this law as evidence that there was no recognized individual right to keep and bear arms in Boston--three years before Congress adopted the Second Amendment: "This is a law that effectively makes it illegal in the city of Boston to have a loaded firearm. To have a loaded firearm in the city of Boston in the 1780s is against the law. The founding fathers were willing to ban loaded guns in the city of Boston."7

A careful reading of the statute, however, reveals that its purpose was not a general ban on loaded guns in Boston, but leaving unloaded guns unattended in buildings. The preamble to the law explains: "Whereas the depositing of loaded arms in the houses of the town of Boston, is dangerous to the lives of those who are disposed to exert themselves when a fire happens to break out in the said town...."8 The text does not prohibit carrying loaded firearms within the city of Boston--only taking them into a building--and one could infer from the preamble, the law only prohibited depositing loaded firearms in buildings. As the preamble makes clear, this law was for the protection of those fighting fires, not to prevent criminal misuse of guns, and certainly not to prevent citizens from defending themselves on the streets. Unloading a flintlock firearm (except by firing it) was a considerably more tedious task than with a metallic cartridge weapon. It is easy to see why the city felt that it was appropriate to require guns not be kept loaded and unattended, especially because Boston had little crime at the time--and I suspect few, if any, home invasions.

That Boston's government felt the need for such a law, however, suggests that gun ownership was common enough, and having loaded firearms in one's home or business was common enough, that the city felt a need to pass such a measure. Fires were more common in eighteenth century buildings than today (because all cooking was done over fireplaces), but it seems unlikely that more than 1% of homes burned in any given year. If guns were rare (as some have claimed) and only 10% of homes had a gun, and only 10% of those homes had a loaded gun, the intersection between houses on fire and houses with loaded guns in them would have been very small indeed--an infinitesimal 0.01% chance of a burning house setting off a gun.

It seems likely, based on counts of guns surrendered to General Gage in Boston in 1775, that more than half the households in town had at least one gun in them at the start of the Revolution--and perhaps even more so, after the Revolutionary War was over, and many veterans of the Continental Army were allowed to bring their service muskets home. It is also unsurprising that many homes had loaded guns as well. A man (and in that era, it would generally have been a man, not a woman) who went hunting out of town might well have returned with an undischarged gun, or a gun that he had reloaded, but not fired again. He could not legally fire a gun in Boston to clear it.

Perhaps the more important point of this law--and a reminder of how much one's assumptions color how you read such a law--is the assumption that the law made: it considered the possession of firearms, cannon, mortars, and grenades in private homes to be not only lawful, but common enough that Boston needed to pass a law requiring them to be unloaded when not in use. This law does not sound like a strong argument against an individual right to keep and bear arms. It sounds like a pretty ringing endorsement of the idea that while there were appropriate safety regulations for keeping deadly weapons in your home, no one questioned the right of individuals to own and keep even military weapons in their own homes.

Clayton

E. Cramer is a software engineer and historian. His last book was Concealed

Weapon Laws of the Early Republic: Dueling, Southern Violence, and Moral

Reform (Praeger Press, 1999). His web site is http://www.claytoncramer.com.